Case Report | Vol 11 | Issue 3 | September-December 2025 | Page: 07-10 | Muhammad Kashif Iqbal, Nabeel Sultan

DOI: https://doi.org/10.13107/jaccr.2025.v11.i03.286

Open Access License: CC BY-NC 4.0

Copyright Statement: Copyright © 2025; The Author(s).

Submitted: 28/01/2025; Reviewed: 20/02/2025; Accepted: 07/10/2025; Published: 10/12/2025

Author: Muhammad Kashif Iqbal [1], Nabeel Sultan [1]

[1] Department of Anaesthesia, University Hospitals of Leicester, NHS Trust, Leicester, UK.

Address of Correspondence

Dr Muhammad Kashif Iqbal

Specialty Doctor in Anaesthesia, University Hospitals of Leicester, NHS Trust, Leicester, UK

E-mail: mkashif.iqbal@nhs.net

Abstract

Sodium is the most abundant cation in the extracellular fluid (ECF), accounting for 86% of plasma osmolality [1]. Normal serum sodium concentration is 135-145 mmol/l. Hyponatremia is defined as serum sodium concentration <135 mmol/l. It can be classified as mild (130- 135 mmol/l), moderate (125-129 mmol/l) or severe (<125 mmol/l). Disorders of sodium balance can occur in up to 30% of inpatients and are associated with increased morbidity, mortality and length of hospital stay [2]. Hyponatremia can be acute or chronic and manifest with mild or severe symptoms such as confusion, nausea, and vomiting, cardiorespiratory distress, sleep disorders, seizures and coma due to several factors like diuretics, adrenal disorders and inappropriate use of antidiuretics. Symptoms are less common with serum sodium concentration above 125 mmol/l.

This case report discusses about a 76- year-old patient with a background history of ischaemic heart disease (coronary artery stenting done in 2018), hypertension possibly due to R/renal artery stenosis, type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, osteoarthritis and osteoporosis who developed severe symptomatic hyponatraemia on first post-operative day following vaginal hysterectomy under spinal anaesthesia and sedation.

Keywords: Severe Symptomatic Hyponatremia, Postoperative

Introduction

Hyponatreamia, with a serum sodium level <135 mmol/l, is the most common electrolyte disorder, reported in approximately 1% of the general population, in up to 15-20% of all patients in urgent care facilities and in up to 30% of all patients treated in intensive care facility [3]. Hyponatraemia usually reflects an excess of body water relative to sodium, being classified as hypervolaemic, hypovolaemic or euvolaemic. Sodium is a major determinant of serum osmolality (normal 280-295 mOsm/kg). Neuroendocrine homeostatic mechanisms compensate for high or low sodium intake by altering its renal reabsorption. Such control is closely linked to patient’s volume state, water homeostasis and maintenance of normal osmolality in the ECF.

Case report

Mrs. P, a 76 – year- old woman with a background history of ischaemic heart disease (coronary artery stenting done in 2018), hypertension possibly due to R/renal artery stenosis (MRA evidence), type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, osteoarthritis and osteoporosis was admitted for elective vaginal hysterectomy. She has been taking aspirin 75 mg OD, atorvastatin 40 mg OD, doxazocin 4 mg OD, lercanidipine 10 mg BD, nicorandil 10 mg BD, telmisartan 80 mg OD, bendroflumethiazide 12.5 mg TDS, metformin 500 mg TDS and colecalciferol 400 units/ calcium carbonate 1.5g OD. She underwent vaginal hysterectomy under spinal anesthesia and sedation (2.2 ml of 0.5% heavy bupivacaine + 20 mcg of fentanyl through spinal and 1 mg of IV midazolam). Surgery was uncomplicated. Estimated blood loss was 100 ml. She has received routine post-operative care in the ward.

Mrs. P was doing well and routine antihypertensives were commenced gradually as her blood pressure was high on the operative day. Her post-operative blood results were within normal limits. She was commenced on oral fluids on demand and routine diet in the ward.

On the first post-operative day around 8 pm, she was found less responsive. Upon examination, she had no verbal response and was opening eyes to mildly painful stimulus and was localizing the pain with a GCS score of 8/15. Her respiratory rate was 14/min and was maintaining peripheral oxygen saturation of 100% with 4 l/min oxygen through the nasal prongs. Her CRFT was < 2s, pulse rate was 100 bpm, non- invasive blood pressure was 190/86 mmHg, heart sounds were normal and JVP was not raised. Her pupils were size 2 and were reactive to light, muscle tone was normal in all four limbs. Temperature was 37.4 C0. Capillary blood glucose was measured to be 11.1 mmol/l. Drug chart revealed that she had received 30mg of codeine at 11.58 and 10 mg of oral morphine at 01.48. Blood was noted inside her mouth and had the impression of a post ictal state following a seizure. Her venous blood gas revealed evidence of severe hyponatremia with a sodium level of 113 momol/l, lactate level of 7.5 mmol/l as abnormal findings and blood sugar was within the normal limits. HDU admission was planned for close observation and monitoring and CT head was planned by the medical team. No fluid resuscitation was attempted in the ward following the event.

She was admitted to HDU for close monitoring and further management of symptomatic severe hyponatremia. Invasive blood pressure and hourly urine output monitoring was commenced along with the HDU care bundle. Upon admission she was conscious and rational and GCS was 15/15. No signs of dehydration were noted. But her fluid balance revealed a negative balance of 700ml. Peripheral oxygen saturation was 97% on room air and her haemodynamics were stable. Serum and urine were sent for osmolality studies and urinary sodium. Thiazide diuretic was withheld. Arterial blood gas results upon HDU admission revealed a sodium level of 115 and potassium level of 3.1 mmol/l. Sodium correction was commenced with 2.7% sodium chloride via a large peripheral cannula at a rate of 20 ml per hour. Potassium replacement was commenced with 40 ml of 0.9% NaCl + 40 mmol KCL per hour. Patient had a witnessed generalized tonic clonic seizure about 3 hours after HDU admission while on sodium replacement. Hourly serum sodium concentration was monitored through the arterial blood gas sampling and hypertonic sodium replacement was discontinued after 6 hours as serum sodium concentration was 120 mmol/l after 6 hours. Meantime patient was referred to the endocrine team. Her serum and urine osmolality results were 255 mOsm/kg and 89 mOsm/kg respectively. Urinary sodium concentration was 17 mmol/l. Fluid balance chart showed a negative balance of 500 ml. CT head

was performed and found to be norm al. Her thyroid functions including TSH and free T4 revealed normal results.

On the second post-operative day patient was conscious and rational and commenced on normal diet. Her sodium level was 130 mmol/l and transferred forward based care.

Discussion

There could be different outcomes of severe hyponatremia, from complete recovery to permanent neurological sequelae and even death. The symptoms of hyponatremia are related to the plasma concentration of sodium and the rapidity of the change of the plasma concentration. The presence of the symptoms and the rapidity of the onset and the duration guide the treatment strategies [4].

Hyponatremia could occurs via three different mechanisms,

1. Acquiring water in a state of isolation; the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH), administration of dextrose infusion

2. Gaining water to a greater extent than gaining sodium; liver failure, congestive cardiac failure, nephrotic syndrome

3. Sodium depletion to a greater extent than that of water

a. Renal; cerebral salt wasting syndrome, diuretics

b. Non –renal; gastrointestinal losses, cutaneous losses (sweating) or so called third space losses ( burns, pancreatitis and trauma)

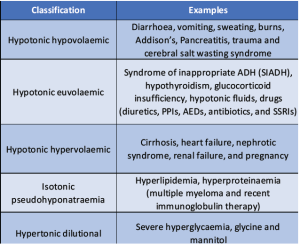

According to the tonicity of plasma hyponatremia could be further classified as hypertonic (dilutional), isotonic (pseudohyponatraemia), or hypotonic (which may be hypervolaemic, euvolaemic, or hypovolaemic).

Proper clinical assessment including full history with past medical conditions, present related incidents, drug history, drinking habits and the fluid balance are important. Examination should focus on the assessment of the volume status, evidence of oedema and clinical signs of other disease processes which could lead to hyponatremia. Proper biochemical assessment is also of value. Investigations including urea and electrolytes, serum and urine osmolalities, TSH, ACTH, cortisol and urinary sodium should be performed. Apart from these, additional investigations could be guided by the relevant history and examination findings.

In our patient, there could be different causes for hyponatremia including congestive cardiac failure, usage of diuretics or due to the third space loss following surgery. As this patient is already diagnosed patient with ischaemic heart disease, perioperative ischaemic event might have been precipitated a heart failure where there is water in excess of sodium. Inappropriate diuretic treatment to treat hypertension and third space losses following surgical trauma might also have contributed. In the absence of chest pain and electrocardiographic evidence of myocardial ischaemia, congestive cardiac failure could be ruled out here. Further presence of a negative fluid balance indicates a state of hypovolemia in our case.

When considering the treatment of a hyponatremic patient, four issues must be addressed; the risk of osmotic demyelination, the appropriate rate of correction to minimize the risk, the optimal method of raising the plasma sodium concentration and estimation of the sodium deficit if sodium is to be given [5]. In chronic hyponatremia (onset >48 hours or unknown), the adaptations returns the brain volume towards normal and protects from the development of cerebral oedema. But in acute hyponatremia (onset <48 hours), rapid sodium correction could lead to osmotic demyelination syndrome as there is no enough time for the adaptations to be taken place

In chronic hyponatremia, the available evidence suggests to elevate the plasma sodium concentration at a maximum rate of 10-12mmol/l during the first 24 hours [6]. However, neurologic symptoms could develop even at this rate and should be cautious during the correction phase [7].

In acutely hyponatremic patient with a sodium level <130 mmol/l who have any symptoms that might be due to increased intracranial pressure (seizures, obtundation, coma, respiratory arrest, headache, nausea, vomiting, tremors, gait or movement disturbances or confusion), like in our patient who had episodes of seizures, treatment with a 100 ml bolus of 3% sodium chloride followed if symptoms persists up to 2 additional boluses of 100 ml, each bolus infused over 10 minutes is recommended. The goal of therapy is to rapidly increase the serum sodium by 4 to 6 mEq/l over a period of a few hours. Raising the sodium by 4-6 mEq/l should generally alleviate symptoms and prevent herniation [8].

Conclusion

This patient had several possible causes of hyponatremia. Sodium level of 113 mmol/l with the presence of witnessed seizures suggests the presence of severe symptomatic hyponatremia. As the patient’s pre – operative serum sodium concentration was normal (139 mmol/l), this suggests acute hyponatremia which requires prompt and active correction to prevent harmful neurological sequelae.

References

1. C Hirst, A Allahabadia, J Cosgrove, The adult patient with hyponatraemia, Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Volume 15, Issue 5, Page 248-252, October 2015

2. Tijan Icin, Millic Medic- Stojanoska, Tatjana IIic, Viadimir Kuzmanovic, Bojan Vukovic, Ivanka Percic, Multiple Causes of Hyponatraemia, A Case Report; Med Princ Pract (2017) 26 (3): 292–295.

3. Yin Ye Lai, Intan Nureslyna Samsudin, Persistent Hyponatraemia in a Elderly Patient, Clinical Chemistry, Volume 66, Issue 5, May 2020, Pages 652–657,

4. Kumar S, Berl T, Sodium , Lancet, 1998; Jul 18;352(9123):220-8.

5. Jameela Al- Salman, Hyponatraemia, Case Report West J Med 2002 May; 176(3): 173– 176.

6. Laureno R, Karp BI, Myelinosis after correction of hyponatraemia. Ann Intern Med 1997; Jan 1;126(1);57-62.

7. Sterns RH, Severe symptomatic hyponatraemia; treatment and outcome; a study of 64 cases, Ann Intern Med 1987;107; 656-664

8. Sterns RH, Nigwekar SU, Hix JK. The treatment of hyponatremia. Semin Nephrol 2009; 29:282.

| How to Cite this Article: Iqbal MK, Sultan N. A 76 –Year- Old Patient with Severe Symptomatic Hyponatremia. Journal of Anaesthesia and Critical Care Case Reports | September-December 2025.11(3):07-10. |

(Article Full Text HTML) (Download PDF)