Case Report | Vol 11 | Issue 3 | September-December 2025 | Page: 01-06 | Aparna Sinha, Misha Katyal, Dinesh Punhani, Abhishek Sharma, Sangeetha Patro, Neha Gupta

DOI: https://doi.org/10.13107/jaccr.2025.v11.i03.284

Open Access License: CC BY-NC 4.0

Copyright Statement: Copyright © 2025; The Author(s).

Submitted: 06/07/2025; Reviewed: 02/08/2025; Accepted: 01/11/2025; Published: 10/12/2025

Author: Aparna Sinha [1], Misha Katyal [1], Dinesh Punhani [1], Abhishek Sharma [1], Sangeetha Patro [1], Neha Gupta [1]

[1] Department of Anesthesiology, Max Super Speciality Hospital, Saket 2, Press Enclave Road, Saket New Delhi – 110017, India

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Aparna Sinha,

Principal Director, Anesthesiology, Max Super Speciality Hospital, Saket 2, Press Enclave Road, Saket New Delhi – 110017, India.

Email: apsin@hotmail.com

Abstract

Background: Difficult mask ventilation (DMV) is a critical challenge during induction of general anesthesia, particularly in patients with obesity, edentulism, or facial hair. Conventional face mask ventilation often fails due to poor seal and anatomical constraints. This study evaluates a nasopharyngeal airway (NA) connected to a breathing circuit as an alternative approach in patients with predicted DMV.

Methods: This prospective observational study enrolled 108 adult patients with predictors of DMV undergoing elective laparoscopic surgery under general anesthesia. After standard induction, mask ventilation was attempted, followed by NA ventilation using a standard endotracheal tube connector. Tidal volume leak, success of ventilation, and patient-specific anatomical variables were recorded. Leak <50% of desired tidal volume was considered successful ventilation. Statistical comparisons were made using paired t-tests and regression analyses.

Results: One patient was excluded due to failed NA insertion. Among the 107 patients analyzed, NA significantly reduced mean tidal volume leak from 43.5% (SD 35.1%) during conventional mask ventilation to 4.7% (SD 5.7%) (p < 0.001). Ventilation success improved from 57% with conventional mask ventilation to 100% with NA. Subgroup analysis revealed the greatest benefit in patients with beards, increased age, and edentulous status. Linear regression identified beard presence (+40.9%, p = 0.002), increasing age (+0.71%/year, p = 0.001), and shorter ventilation time as significant predictors of leak reduction. Adverse events were minimal (4.5%), including two cases of transient desaturation and one nasal bleed, all self-limiting.

Conclusion: Nasopharyngeal airway connected to a ventilator circuit is a highly effective and safe alternative to conventional mask ventilation in patients with anticipated DMV. Its efficacy is particularly notable in anatomical profiles associated with high mask leak.

Keywords: Nasopharyngeal airway, Difficult mask ventilation, Airway management, Obesity, Beard, Edentulous, Ventilation leak

Introduction

Effective mask ventilation is a cornerstone skill for anesthesiologists, being not only the initial step in general anesthesia but also a crucial backup when intubation fails. The incidence of difficult mask ventilation (DMV) is approximately 1.4% 1, while impossible mask ventilation occurs in about 0.15% of cases [1, 2]. Ensuring successful ventilation is thus critical to prevent hypoxemia and serious complications.

In patients with known predictors such as obesity, edentulous state, presence of beard, or anatomic variations like large tongue or reduced mandibular space, managing DMV poses considerable challenges, particularly. Herein, we present an innovative approach using a nasopharyngeal airway connected to a breathing circuit through an endotracheal tube connector (Fig. 1). This assembly allows unobstructed breathing, accurate end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring, and effective assisted ventilation when required.

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee, and a waiver of written informed consent was obtained due to the observational nature and minimal risk involved in the intervention. Verbal informed consent was obtained following approval by the Institutional Ethics Committee under the waiver provisions outlined in ICMR 2017 guidelines. All procedures followed institutional and international ethical guidelines for human research.

Methods

We enrolled 108 consecutive adult patients scheduled for elective laparoscopic surgery under general anesthesia with anticipated DMV. Inclusion criteria were: age between 18 to 80 years, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I-III, presence of at least one of the known predictors of DMV during pre-anesthesia assessment, Body mass index (BMI) >35 kg/m², Neck circumference (NC) >40 cm, edentulous state, presence of beard, Mallampati grade III/IV and upper lip bite test (ULBT) grade II/III.

The inclusion of anatomical and demographic predictors in this study was guided by validated evidence from large cohort analyses. Kheterpal et al. (2006) identified age > 55 years, BMI > 30 kg/m², edentulism, beard, and male sex as independent predictors of difficult mask ventilation in over 22,000 anaesthetics 1. Their subsequent study of 50,000 cases confirmed that combinations of these factors, particularly obesity and facial hair, markedly increased failure risk 2. Kim et al. (2011) introduced the neck-circumference-to-thyromental-distance ratio as a quantitative index of upper-airway bulk in patients with obesity. These validated parameters formed the rationale for our inclusion criteria, ensuring enrollment of a clinically relevant cohort with anticipated difficult mask ventilation.

Exclusion criteria included deviated nasal septum, inadequate nasal patency, risk of aspiration, history of nose bleed, deranged coagulation, thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, chronic renal failure, previous exposure to radio therapy or any requirement for planned awake fiberoptic intubation.

Preoperative Assessment and Preparation

Nasal patency was assessed preoperatively, along with a full airway evaluation including ULBT. Premedication included oral pantoprazole 40 mg administered two hours before surgery with minimal water. Patients were positioned such that their external auditory meatus aligned horizontally with the suprasternal notch [3].

Standard monitoring included ECG, non-invasive blood pressure, pulse oximetry, end-tidal carbon dioxide, and expired tidal volume (VTe) measurements.

Anesthetic Management

Preoxygenation was achieved using twin nasal prongs at 6 L/min with aim to achieve EtO2 >0.9. In patients with anticipated difficult mask ventilation, the ability to achieve an effective facemask seal is uncertain. Continuous oxygen flow via nasal cannula helps maintain apneic oxygenation during induction and early airway management, minimizing desaturation risk. This approach is supported by the ASA 2022 and Difficult Airway Guidelines, both recommending maintenance of nasal oxygen delivery during apnea in anticipated difficult airway scenarios. Thus, nasal prongs provided a safety bridge between preoxygenation and nasopharyngeal ventilation, ensuring uninterrupted oxygenation without interfering with airway instrumentation.

Induction was performed with propofol via target-controlled infusion (TCI) to achieve an effect-site concentration of 3–3.5 µg/ml, midazolam (0.01 mg/kg), fentanyl 2 mcg/kg) based on lean body weight.

Once the eyelash reflex was lost, ventilation was initiated using a properly fitting face mask. Target tidal volume (TVt) and maximum achieved expiratory tidal volume (TVe) over the next ten breaths were recorded, along with any SpO₂ changes.

A lubricated nasopharyngeal airway, adapted with an endotracheal tube connector, was then placed into the more patent nostril and attached to a volume-controlled ventilator. Nasopharyngeal airway sizing: ID 7 mm, 7.5 mm, or 8 mm, corresponding to ET connectors of the same ID, as appropriate. (Fig. 1)

A two-hand technique was employed with thumb pinching the open nostril

The fingers were used to perform a jaw thrust while simultaneously sealing the lips together (Fig. 2). Effective ventilation was confirmed through a square capnograph waveform, bilateral chest rise, and measurable expiratory tidal volume. Time to ventilation (TTV) was defined as the duration after inserting the NA to the appearance of a capnograph waveform.

Data Collection

While leak percentage was the primary outcome, secondary outcomes including capnographic waveform quality, time to effective ventilation (TTV), visible chest excursion, and adverse events were prospectively recorded to strengthen clinical interpretation.

These secondary outcomes were selected to provide a multidimensional view of ventilation effectiveness. Capnographic waveform quality served as an objective indicator of alveolar ventilation, while time to effective ventilation (TTV) reflected the rapidity of achieving functional ventilation—crucial in patients with obesity who desaturate quickly. Visible chest excursion provided an easily observable clinical correlate, and adverse events such as desaturation, nasal trauma, or need for adjunct devices were recorded prospectively to evaluate the safety and feasibility of the nasopharyngeal ventilation technique. Further other parameters recorded were patient demographics, desired tidal volume (TVst) and achieved tidal volume (TVe), SpO2 , baseline vitals, any post extubation nasal bleed or discomfort [4]. Experienced anesthesiologists standardized all procedures. In cases of unsuccessful nasal airway ventilation, supraglottic airway devices were used, and the ASA difficult airway algorithm was followed [4].

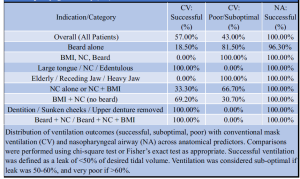

Successful ventilation was defined as a leak of <50% of desired tidal volume. Ventilation was considered sub-optimal if leak was 50-60%, and very poor if >60%.

Statistical Methods

Data was analyzed using descriptive statistical method. Continuous variables such as age, BMI, neck circumference, and leak percentages were summarized as mean, standard deviation (SD), minimum, and maximum values. Paired comparisons between conventional mask ventilation (CV) and nasopharyngeal airway (NA) were performed using the paired t-test to assess differences in mean leak percentages. Categorical outcomes (successful, suboptimal, poor ventilation) across anatomical predictors were compared using the chi-square test. A linear regression analysis was done on variables found significant in the univariate analysis. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and Observations

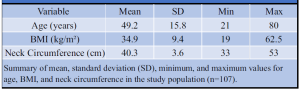

A total of 108 patients were included in the study. However, one patient had a failed nasal airway , hence it was excluded from the study. The demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 49.2 ± 15.8 years, the mean BMI was 34.9 ± 9.4 kg/m², and the mean neck circumference was 40.3 ± 3.6 cm.

We observed a significant reduction in ventilation leak when switching from conventional mask ventilation (CV) to nasopharyngeal airway (NA) ventilation.

The mean leak during CV was 43.5.0% (SD 35.1%), whereas the mean leak during NA ventilation was substantially lower at 4.7% (SD 5.7%). This difference was statistically significant (paired t-test, t = 11.61, p < 0.001) .

Overall the mean % leak with CV and mean % leak with NA differ significantly (P-value < 0.001). The average percentage leak during CV was high (mean 43.5.0%), with a considerable proportion of patients (36.4%) experiencing poor ventilation. In contrast, NA ventilation achieved a mean leak of only 4.7%, with 100% of patients achieving successful ventilation (<50% leak). This absolute improvement from 57% to 100% success following NA use is both statistically and clinically significant (Table 2, 3 ).

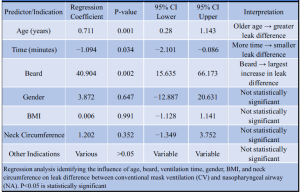

To determine which patient factors significantly contributed to the improvement in leak (%) when switching from conventional mask ventilation (CV) to nasopharyngeal airway (NA) a logistic regression of difference in leak (%) on age, gender, time, BMI, NC, edentulous state and beard was performed, table 2.

Linear regression identified age, time, and the presence of beard as significant predictors of leak difference between CV and NA. Older age was associated with a greater reduction in leak, while shorter mask ventilation time correlated with larger improvements. Among all anatomical predictors, the presence of a beard contributed most significantly to leak reduction, with a coefficient of +40.9 (p = 0.002), underscoring its impact on poor mask seal and the value of early transition to nasopharyngeal airway.

The factors in table 3 together are significantly (P < 0.001) contributing to the difference in leak but their total contribution was small (R2 = 0.299 which is nearly 30%) : This implies that predictors explain about 30% of the variance in leak reduction. This is moderate strength and implies that other unmeasured factors may still be playing a role.

Secondary outcome analysis supported the clinical efficacy of nasopharyngeal ventilation. A stable square-wave capnographic trace was achieved rapidly after induction, confirming effective alveolar ventilation. Visible chest excursion was observed in all patients, and no adverse events such as nasal bleeding or airway trauma were reported. No patient required escalation to a supraglottic device for rescue ventilation. These findings reinforce the practical safety and reliability of the technique in the early peri-induction period.

These findings confirm that the use of a nasopharyngeal airway connected to a ventilator significantly improves ventilation efficacy by minimizing leak, thereby enhancing patient safety during airway management in predicted difficult mask ventilation scenarios.

Adverse events were observed in 4.5% of the study population, with 95.5% reporting no complications. The most frequently documented events included transient desaturation during mask ventilation, with SpO₂ dropping to 90% and 92% in two separate cases, and one instance of mild nasal bleeding. All events were self-limiting and did not require escalation of care.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of a nasopharyngeal airway (NA) as an alternative to conventional mask ventilation (CV) in patients anticipated to have difficult mask ventilation.

Our findings demonstrate that NA significantly reduces ventilatory leak and results in a remarkable improvement in ventilation outcomes.

Our study adds to the increasing body of evidence suggesting that nasopharyngeal airway (NA) ventilation yields better outcomes in patients with predictors of difficult mask ventilation (DMV). In a randomized crossover trial, nasopharyngeal ventilation yielded significantly improved tidal volumes and ventilation success in high-risk patients compared to facemask ventilation [5, 6]. Similarly, we observed an absolute improvement in success from 57% with conventional mask to 100% with NA, including in subgroups with anatomical risk factors such as beards, increased neck circumference, and edentulous state.

Consistent with previous studies, our data reaffirm that DMV is more common in individuals with BMI >30 kg/m², age over 57 years, and especially those with facial hair [6, 7]. Neck circumference, which has been independently associated with both difficult intubation and mask ventilation in patients with obesity, could be successfully managed with NA in this study, likely due to the device bypassing soft tissue compression [7].

Anatomical predictors such as beard, increased neck circumference (NC), higher BMI, edentulous status, and altered facial anatomy (receding or heavy jaw) were associated with poor or suboptimal ventilation with CV. Importantly, the efficacy of the NA in edentulous patients supports earlier findings that nasal ventilation is advantageous in cases where orofacial seal is compromised [7, 8]. These results also mirror observations in noninvasive ventilation settings, where mask leak poses significant clinical challenges and nasal routes have been proposed to mitigate seal-related failures [8, 9].

Nasopharyngeal ventilation has a physiological advantage since it can send positive pressure directly into the pharyngeal space, distal to the soft palate and base of the tongue, avoiding upper airway collapsibility. This method avoids the dynamic obstruction that frequently happens during anesthesia induction, especially in individuals who are obese or have edentulous anatomy, as these conditions make the tissues of the upper airways more likely to collapse. Nasopharyngeal ventilation improves alveolar ventilation efficiency by placing the airflow deeper in the airway and reducing the anatomic dead space that facemask ventilation causes. Despite challenging mask seal conditions, the outcome is more consistent tidal exchange, reduced leak volumes, and more efficient oxygen supply. The improvements in tidal volume and leak reduction that we found in our study can be explained by these mechanisms taken together.

Patients with beards—whether alone or combined with nasal congestion (NC) and elevated BMI—experienced failure rates above 80% with conventional ventilation (CV). In contrast, the use of a nasopharyngeal airway (NA) achieved 100% ventilation success across all anatomical groups studied, highlighting its reliability in difficult airway conditions. Older patients showed greater reductions in ventilatory leak when switched to NA, indicating that efficacy may improve with advancing age. Moreover, shorter mask ventilation times correlated with greater leak reduction, reflecting timely recognition of inadequate CV and early transition to NA.

Beyond categorical anatomical predictors, morphometric ratios have also been shown to refine airway risk assessment. Kim et al. demonstrated that the neck-circumference-to-thyromental-distance (NC/TMD) ratio provides a superior predictor of difficult intubation in patients with obesity compared with individual parameters such as BMI or neck circumference alone. Their findings suggest that upper-airway bulk relative to mandibular space is a key determinant of airway difficulty. This principle likely extends to mask ventilation, where reduced mandibular space and excessive soft-tissue mass compromise orofacial seal and ventilation efficiency. The present study supports this concept by showing that patients with increased neck circumference and reduced mandibular space benefitted most from nasopharyngeal ventilation, highlighting the shared anatomical basis between difficult intubation and difficult mask ventilation. Among anatomical predictors, the presence of a beard was the most influential factor: these patients had the largest leaks with CV but demonstrated the most marked improvement when ventilated via NA. These results confirm NA as a highly effective strategy for managing predicted difficult mask ventilation and stress its importance in scenarios where anatomical or patient-related factors limit the success of conventional techniques.

The incorporation of secondary outcomes provided clinically relevant context to the observed reduction in leak percentage. Rapid appearance of square-wave capnography and consistent chest excursion indicate that nasopharyngeal ventilation not only reduces leak but ensures functional gas exchange. The absence of complications such as desaturation or trauma further supports the safety of the technique in high-risk populations. These findings underscore that assessing ventilation quality through integrated physiological and clinical markers offers a more complete understanding of airway performance than leak metrics alone.

Our findings support the role of NA as a dependable rescue modality in patients with obesity, elderly individuals, those with beards, and edentulous patients—situations where achieving a mask seal or performing an effective jaw thrust can be challenging. The study provides quantifiable evidence of leak reduction and clinical efficacy with NA compared to CV across a broad spectrum of difficult airway predictors. Importantly, NA consistently rescued patients, achieving 100% success even in high-risk groups such as elderly patients with receding jaws and edentulous profiles who could not be ventilated effectively with CV. Ventilation outcomes with NA were uniformly excellent across all anatomical challenges.

Supraglottic devices such as the LMA ProSeal and i-gel are proven rescue airways that offer reliable oxygenation once inserted but require deeper anesthesia, mouth opening, and oropharyngeal manipulation—steps that may be challenging or unsafe during the early phase of anticipated difficult mask ventilation. The nasopharyngeal airway, by contrast, enables immediate oxygenation and ventilation through a non-oral route, maintaining airway patency without disrupting laryngoscopic preparation. This positions NA as a valuable bridge technique or early step before SGA insertion, consistent with the escalation sequence described in the ASA 2022,4 and Difficult Airway Society Guidelines and supported by recent evidence 5 demonstrating superior ventilation efficacy of nasopharyngeal compared with facemask techniques. Integrating NA into the early stages of airway management may therefore shorten the time to effective ventilation and reduce desaturation risk before definitive SGA or tracheal access.

While the DAS 2015 guidelines remain foundational in managing unanticipated difficult intubation, more recent DAS documents—such as the 2020 guidelines on awake tracheal intubation in adults—emphasize maintaining oxygenation during all airway interventions, limiting attempts, and early adoption of rescue strategies. The concept of apneic oxygenation and graduated airway escalation inherent in these guidelines supports the rationale for nasopharyngeal ventilation as an early oxygenation bridge [4, 5, 9, 10].

Conclusion

Our study shows that connecting a nasopharyngeal airway to the ventilator circuit delivers markedly better ventilation than conventional mask ventilation, primarily through substantial leak reduction. This straightforward and reliable approach offers a valuable alternative for anticipated difficult mask ventilation, improving success rates and reinforcing patient safety.

References

1. Kheterpal S, Han R, Tremper KK, Shanks A, Tait AR, O’Reilly M, et al. Incidence and predictors of difficult and impossible mask ventilation. Anesthesiology. 2006 Nov;105(5):885–91. doi:10.1097/00000542-200611000-00006.

2. Kheterpal S, Marin L, Shanks AM, et al. Prediction and outcomes of impossible mask ventilation: a review of 50,000 anesthetics. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:891-897.

3. Sinha A, Jayaraman L, Punhani D, Panigrahi B. ProSeal laryngeal mask airway improves oxygenation when used as a conduit prior to laryngoscope guided intubation in bariatric patients. Indian J Anaesth. 2013;57(1):25-30.

4. Apfelbaum JL, Hagberg CA, Connis RT, Abdelmalak BB, Agarkar M, Dutton RP, Fiadjoe JE, Greif R, Klock PA Jr, Mercier D, Myatra SN, O’Sullivan EP, Rosenblatt WH, Sorbello M, Tung A. 2022 American Society of Anesthesiologists Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2022 Jan;136(1):31–81. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000004002. PMID: 34762729.

5. Lenhardt R, Akca O, Obal D, Businger J, Cooke E. Nasopharyngeal Ventilation Compared to Facemask Ventilation: A Prospective, Randomized, Crossover Trial in Two Different Elective Cohorts. Cureus. 2023 May 15;15(5):e39049. doi: 10.7759/cureus.39049. PMID: 37323341; PMCID: PMC10266899.

6. Kim WH, Ahn HJ, Lee CJ, Shin BS, Ko JS, Choi SJ, et al. Neck circumference to thyromental distance ratio: a new predictor of difficult intubation in obese patients. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106(5):743–8. doi:10.1093/bja/aer024.

7. Saito T, Taguchi H, Asai T. A randomized controlled trial of nasal airway ventilation in edentulous elderly patients. Anesth Analg. 2010;110(5):1232–5. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181d6d5f8.

8. de Almeida JP, Silva AR, Torres Dde S, Galvão MC, Costa RM, Viana KD. Mask leakage during noninvasive ventilation: clinical factors and predictive analysis. Respir Care. 2017;62(10):1355–62. doi:10.4187/respcare.05258.

9. Frerk C, Mitchell VS, McNarry AF, Mendonca C, Bhagrath R, Patel A, et al. Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115(6):827–848. doi:10.1093/bja/aev371. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aev371

10. Irwin MG. Difficult Airway Society guidelines for awake tracheal intubation in adults. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(5):688. doi:10.1111/anae.14969. PMID: 32557546. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14969

| How to Cite this Article: Sinha A, Katyal M, Punhani D, Sharma A, Patro S, Gupta N. Novel Technique of Nasopharyngeal Airway as an Alternative to Conventional Mask Ventilation in Challenging Airway. Journal of Anaesthesia and Critical Care Case Reports | September-December 2025.11(3):01-06. |

(Article Full Text HTML) (Download PDF)